CICAEDIA Spring / Summer 2024: Shuttle to PATHOS-2.

The collection came from the feeling of being slightly out of sync with the world around me. It started the way most of my work does, in a moment of dissociation. I was on the L train, watching my reflection in the window. The lights flickered, the tunnel kept going, and for a second my face didn’t look like mine. I was still, but moving. That fracture, watching yourself from outside yourself, became the emotional starting point.

I kept returning to SOMA, the 2015 psychological horror game by Frictional Games. I first played it in 2018, and since then it’s followed me. I’ve replayed it, re-watched seven-hour no-commentary runs, sometimes looping them for days while I sewed. It stopped being background noise and started to feel like internal noise. The horror in SOMA isn’t about monsters. It’s about losing the sense of what makes you human. Consciousness trapped in machinery. Identity glitching inside simulation. That felt familiar.

I remember explaining the early plans for this show to one of my professors, who immediately tried to talk me out of it. It was an interesting but consistent theme throughout my time at Parsons, professors who expected you to already have a label by your third year, yet constantly dissuaded you from doing anything ambitious outside of class (unless it was for someone else). They wanted restraint when I was trying to build momentum. The contradiction became its own kind of motivation. It felt like the first real disillusionment, realizing that the system teaching you creativity often wanted to contain it.

This collection was also much more thoroughly designed than it was executed. The sketches for it, which still exist and are available upon request, show a far more refined vision than what I was able to produce physically. As the industry moves faster into digitization, I feel myself moving in the opposite direction. I still cut, drape, and pin everything by hand. I rely on construction, the discipline of it, the quiet control. The architecture of Givenchy’s early couture still matters to me, not because of nostalgia but because of its patience. Those garments were designed to remember. I try to work the same way.

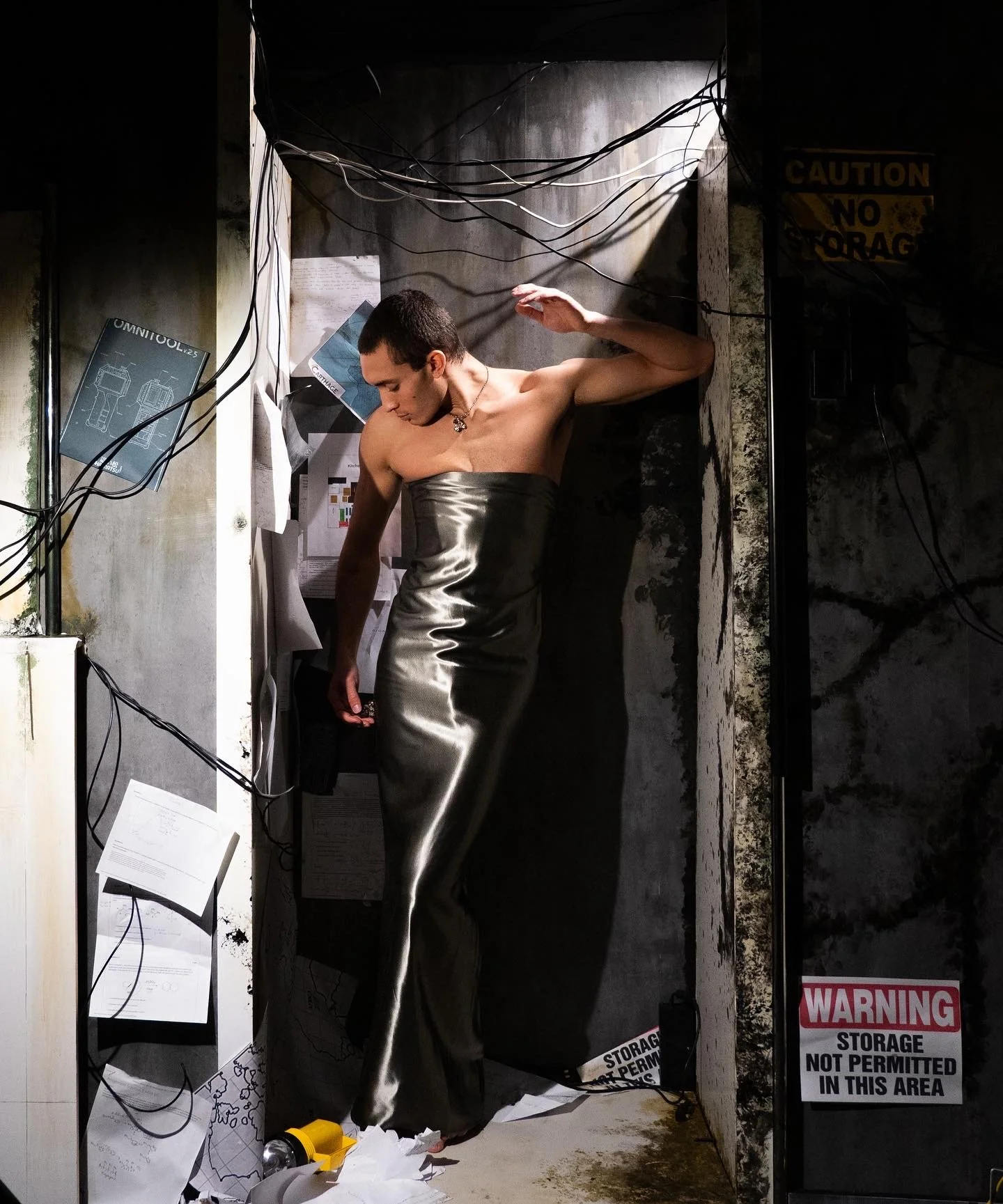

The collection opens in grey; the uniform and stylistic foundation of the CICAEDIA woman. Simplistic jersey skirts and cropped tanks mix with dresses styled over pencil skirts or worn alone. The result is quietly sensual, though minimal. Fitted, but deliberate. The silhouettes are controlled without feeling stiff.

Jewelry and detailing in this section are focal: with white and black beads scattered across and styled into certain looks. When I first saw the white beads, they reminded me of the oval LED lights from SOMA. I decided to treat them as such, white as “on,” black as “off.” Some outfits were fully blacked out, as if the power had gone out completely. Some of the beads hung from chains, others were tied on rope. Later, I found larger wooden beads that I hand-painted black and used on shorts and necklaces. The necklaces carried a mix of West Coast meets East Coast minimalism, almost rustic in execution, styled across the men’s looks that foreshadowed the ethos of the CICAEDIA man.

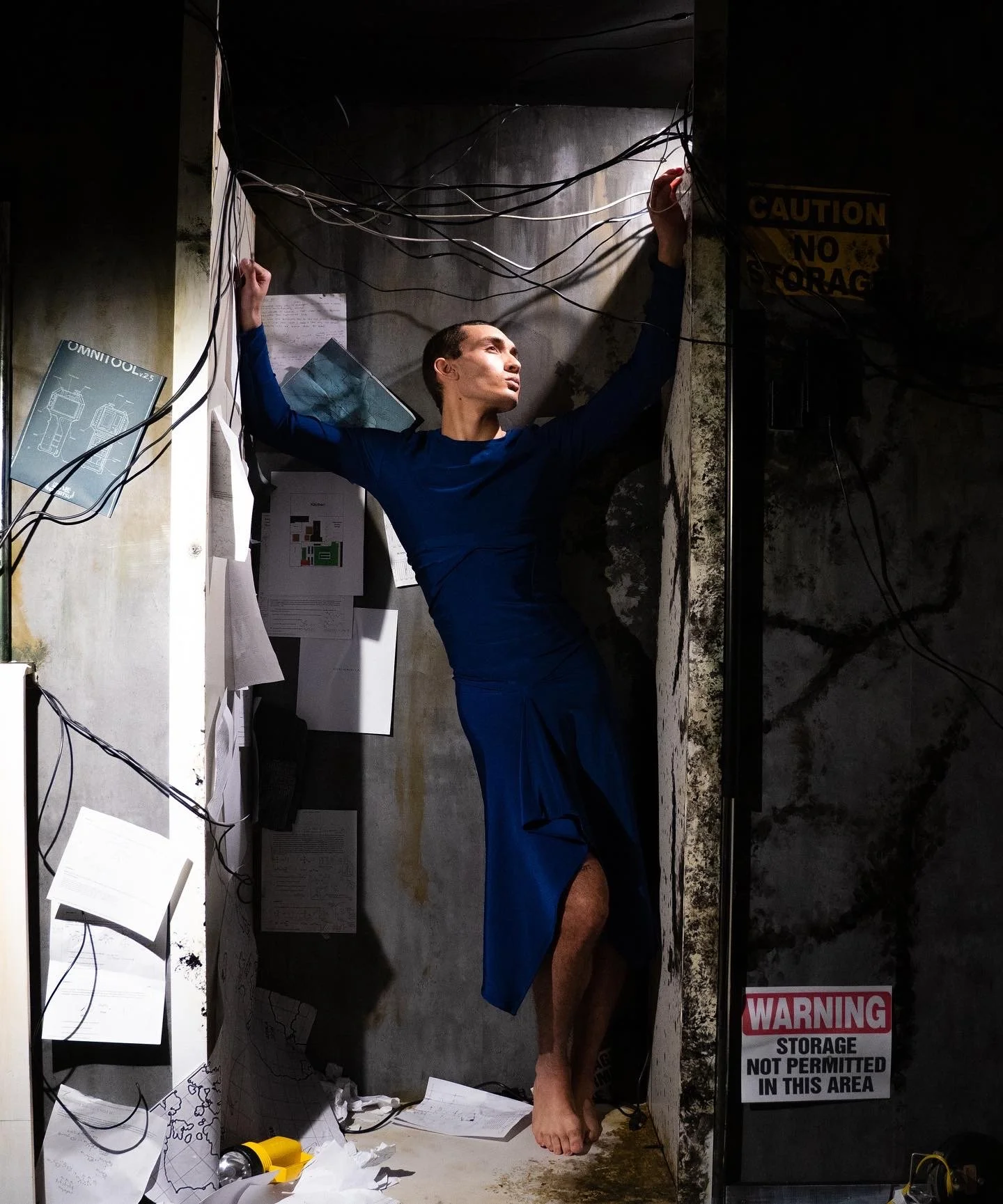

Color then seeps in. Toxic greens and dense ocean blues move through wet velvets, plasticky jerseys, and warped nylon. The palette starts sterile and ends contaminated. These materials mimic strength because they are strong, durable, they don’t decay or dissolve the way natural ones do. They last. Permanence as pollution, if you would. At the time, I was working in an environment obsessed with ethical production, where “sustainability” had become a performance, something overexposed, used to justify lazy work and poor design. It frustrated me. I wanted to play with that contradiction: to make something beautiful out of the materials everyone pretended not to use.

There was one fabric that defined that feeling. A black synthetic textile I found at a mainstream spandex store in the Garment District, unique to that place. Even in person, people mistake it for leather until they touch it. Up close, it’s impossible to identify. It feels as if a plastic chrome coating has been sprayed over deep-dyed nylon. It’s slick, almost artificial to the point of discomfort, with a strange surface scent that fades when worn. I used it everywhere, in the structure of hoodies, full corset dresses, and shorts throughout the mid and later sections. It held its shape like a material pretending to be something else.

At the time, I was also deeply inspired by Balenciaga Fall 2008. As many designers are at some point, I became fascinated by what Nicolas Ghesquière did that season, not only the aesthetic, which was profoundly powerful, but the cut itself. A few years earlier, I had built a pattern block that reversed the classic bust dart into the center of the garment. It’s a simple modification, but it gives a clean, architectural elegance to even basic shapes. The way Nicolas did it in that collection amplified the idea entirely, he pushed a familiar technique into something structural and new. Anything since then feels like imitation. The patternmaking in Shuttle to PATHOS-2, at its best, is a nod to that work.

This was my first show, and it was an insane experience overall. There was no production, no show running. The models had never even been fit. We essentially assembled it live in front of the full guest list. I had to hold the presentation slightly after the Spring 2024 New York Fashion Week season, by then Milan had already started. this was because most of my peers at the time couldn’t make it otherwise. They were caught up in their internships, something I kept refusing to do through the very end of my time in school.

The show took place at Vila Natalia, my family home in Riverdale, NY. My dining room was remodeled for it. I built set walls that partially enclosed the space, creating narrow areas for the models to emerge through. The idea wasn’t to transform it into something unrecognizable, but to distort what was already there. I created a tableau instead of a stage, a single environment that felt like both a home and a lab. The floor was covered in lab equations I stole from my sister. One side of the wall featured blown-up graphics warning about the “black mass,” mimicking the WAU. In reality, it was a hand-painted spiderweb of Mod Podge and sand. It all came together to form a vague visual experience; artificial, textural, faintly unsettling. A domestic space rewritten as a containment scene. I built the entire set alone over the course of three weeks, while sewing the collection and finishing school.

Shuttle to PATHOS-2 was never just science fiction. It is about obsession, about trying to keep something human and emotional alive inside a system deleting that vulnerable part of itself. It’s about the need to sew something tangible while everything around me dissolved into a digital ice-age. It is about memory and touch and what survives when you will not let a feeling die, holding onto something warm and human even when everything around you insists on becoming cold and mechanical. It is my way of saying I am still here. That this is something that still matters. That we can still create something that matters. That I still matter.

Show-Notes Written by Yitzhak Rosenberg

Designed by Yitzhak Rosenberg

Runway Production, Set Design, Styling, & Casting by Yitzhak Rosenberg

Hair & Makeup by Joey DeVirgilio

Runway Photography by Stephanie Rodriguez

Runway Video by Zach Wassef

Campaign shot by Yitzhak Rosenberg.